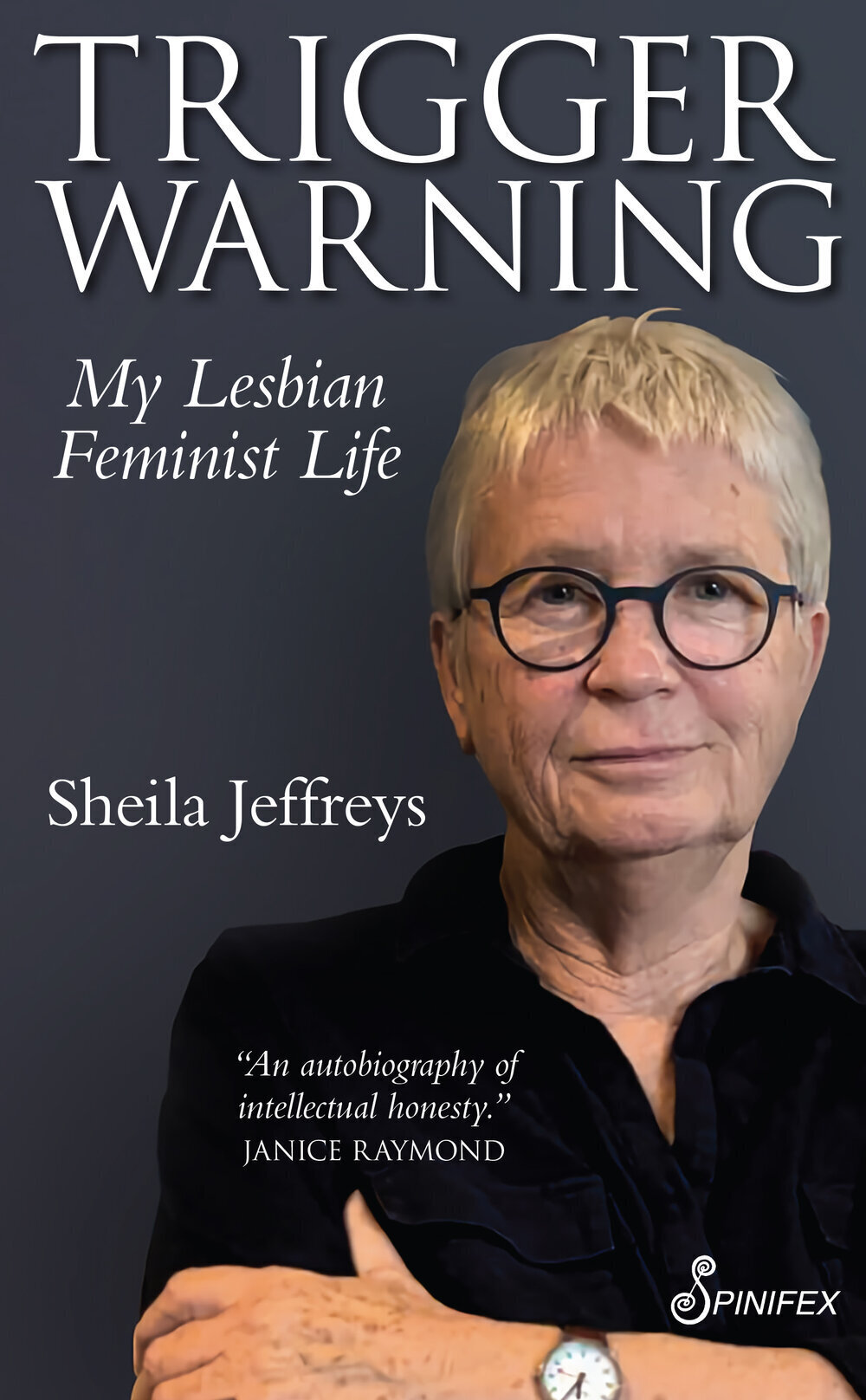

Review: Sheila Jeffreys’s autobiography Trigger Warning: My Lesbian Feminist Life

Are we women ready to wake up?

Trigger Warning: My Lesbian Feminist Life takes you to the revolutionary feminism of the 1970s to the lush Australian nature, down through the desert of the early 2000s all the way to today. But if you think that this time and space travel will make for a light read, you’ve come to the wrong feminist. As always, Sheila Jeffreys tackles major controversies right on. Trigger warning is an occasion for us all to take stock on our achievements and most importantly where we have regressed. So if instead, you want to know why we women must wake up, why our lives depend on a feminist movement, why we must continue the struggle, read this book.

Are we women ready to wake up?

Reading a book by Sheila Jeffreys is always an experience. It’s never just about the knowledge you find in it, but the emotional state it leaves you in. You don’t really shelf it back: you can’t unknow what you have just learnt. Man’s Dominion was a relief. Finally, someone had laid out what I too thought. Unpacking Queer Politics was to me what Teflon is to American culture: can you imagine that we were sold knowingly something whose harms were widely documented ? Anticlimax was a turning point. It took me some time to get into it, as if anticipating the intellectual cataclysm it represents, trying to postpone the point of no return. It read like a novel, as Sheila Jeffreys’s books do. Bolstered by the FiLiA Conference where I bought it, it made men in my life look superfluous and I know the seeds it planted will only grow in the years to come. Although thrown at her as a criticism, as Jeffreys reveals in her autobiography, her capacity to influence other women is undeniable and I am grateful to her for it.

Trigger Warning is insightful, dense, thought-provoking, unapologetic, informative, very Sheila. It covers a tremendous amount of topics, it doesn’t neglect any controversy. An alternative title could have been ‘We wanted theory’. Theory that is not an academic prerogative but the way of making sense of what is happening to us; in theory we find solace. It was therefore surprising to read that Sheila was accused of being too logical. To be fair, if logic made the world go round, feminism would have taken over the world and our job would be done. Now, I don’t want this to end up like a New York Times book review of adjectives skewer (although they tend to combine directly opposite adjectives like ‘enlightening and obscure’) but the book does deserve them. It reads in one go.

The feminist activist starts with her childhood in beautiful Malta as the Daughter of the Sun where she is confronted with male violence for the first time with ‘flashers’. At university in Manchester, she tries to play liberal for a while (to the point where a Frenchman wants to throw his penis away out of embarrassment for not standing up to Sheila’s sexual overzealousness) before finding feminism. Enter the rollercoaster of a life of activism. Despite some criticism and animosity, Sheila Jeffreys’s analysis is heard. From the papers read in small groups in England, to working in the USA meeting her feminist sheroes, settling in Australia and going on a book tour in South Korea, Sheila’s perseverance demonstrates that it is possible to awaken feminist consciousness: none of us were born feminist but if it worked for us there is no reason it shouldn’t for other women. As exhilarating as finding sisterhood and an attentive public is, Jeffreys’s journey is clouded with bouts of depression and anxiety. Most of the time, her analysis is rejected in a passive way: for example, academic recognition is slow to come even when her books were already noticed by the malestream media as she so brilliantly calls it. In other cases, the attacks are more straightforward: pimps come up with slogans referring to Jeffreys, a dildo is named after her, she is bombarded with harassing calls and male whims’ activists invade her classrooms in an attempt to silence her.

Loneliness kicks in as the movement dwindles and she makes it a personal duty to look at the things that no woman wants, namely male violence. She is repeatedly shot for being the messenger, hence the trigger of the title. Her exposure of patriarchy bothers. Women’s ignorance is preferred to our distress. How can I blame any woman for not wanting to realise how much men hate us? The episode in which she was kicked out of a lesbian retreat for having said that referring to a man who murdered his wife (a certain Louis Althusser) for feminist analysis was somewhat inappropriate is just one of the many cases of exclusion she talks about (to be fair that’s not even the worst-case since she is hosted in a gorgeous Italian villa and ends up watching lizards whose potential for entertainment is greatly undervalued and is by all means superior to the reading of men defending men).

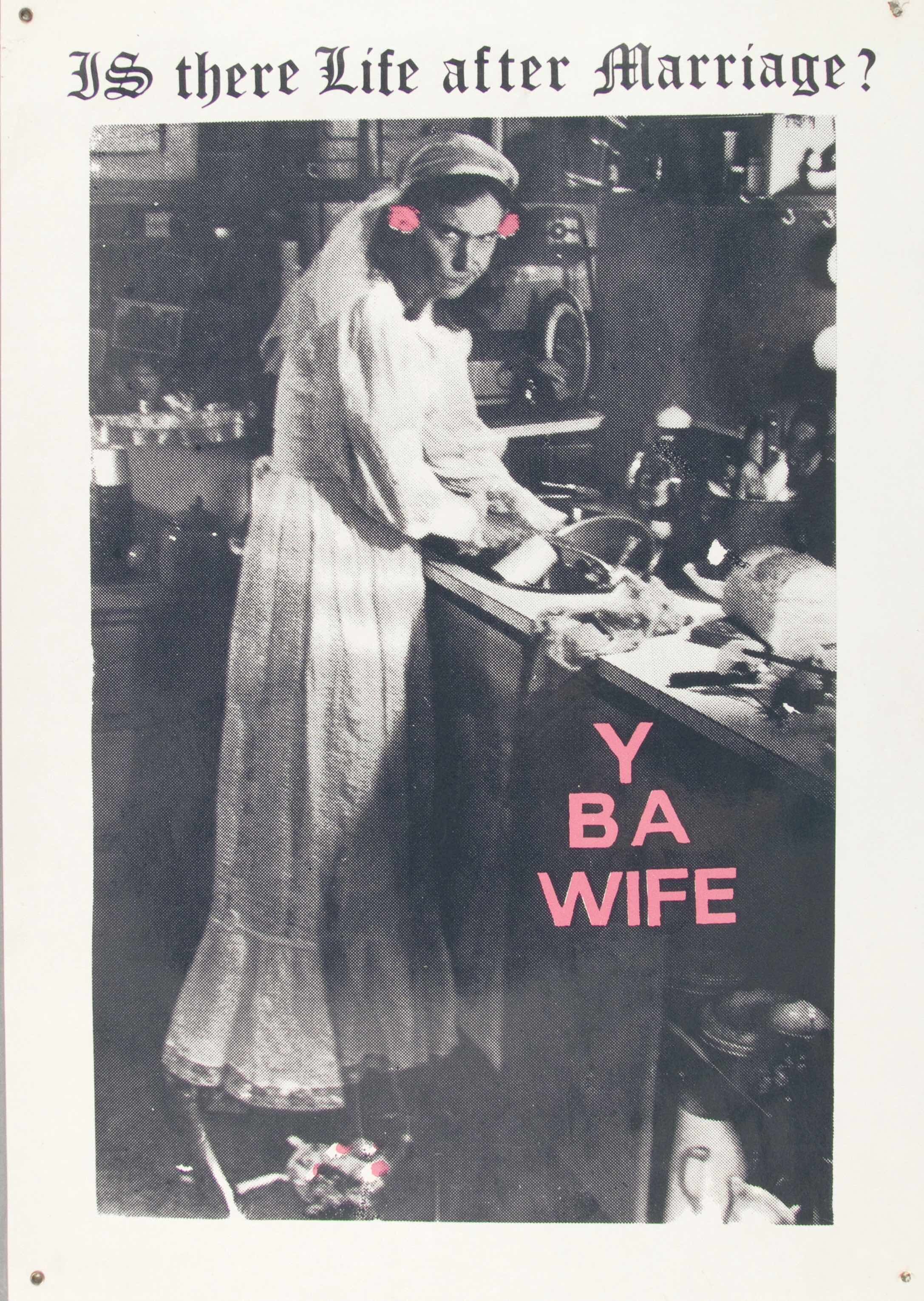

The book is a great introduction to the recent herstory of feminism in the UK. There’s a lot to learn from past methods of organising which leave me in awe of women’s creativity (I think for instance about the Y B A Wife campaign). Jeffreys’s self-deprecating humour throughout (I laughed out loud at: ‘a university newsletter announcing the talk described me as looking as like a “chipmunk and a sprite” alongside a picture in which I do look precisely like that’) gives a sense of how she coped with the difficulties she faced. Indeed, one can only imagine given that she does not expand too much on her internal turmoil, which is a tad frustrating for the reader. But while it is valuable to learn from our elders so as not to reinvent the wheel, what do we do — as Goebbels notoriously put it — when the wheel has turned square?

When our oppression is called our liberation, when the means of expression are appropriated by the dominant sex, we are stuck. Learning about the Khomeinist Revolution in Iran I wondered what it must feel like for women to know the past was better than the present. With Trigger Warning I got a sense of it. We assume progress is ongoing: the next generation being worse off than the previous one seems unnatural, but it does happen. That is not say everything was rosy and perfect back then, far from it but the hurdles were not comparable to the ones we have today.

With pornography we no longer have the benefit of direct action since the exploitation is so dematerialised, we don’t even know what happens in it. Electrocution is what happens. Bounding, gagging, forced eating of faeces, urinating, beating, insulting, forced vomiting, triple penetrating is what happens. If you dare to suggest that men should stop consuming pornography, you’d think from the gasps of astonishment that you asked those poor souls to stop breathing. Yet, actual chocking is called ‘breath play’. Is it any wonder that the generation that grew up with pornography is hooked on sexual sadism? How can we believe that a man can caress you with a knife? That you can play with trust? From Cosmopolitan: ’There were several times in high school when partners would do things with me that I didn’t know were BDSM at the time—like being tied up and controlling me or doing consensual fear play—dragging a knife across my body sensually as a way to take me to the edge of trust with him’. What’s with my generation? Undressing for Instagram, wearing chockers, masturbating at PornHub and date rapes with Tinder?

Critiques of heterosexuality have been wiped away. Equality between heterosexual and homosexual men is pursued through the equal exploitation of women: industrial vagina for the first, wombs for rental for the second.

With the rise of identity politics, we are asked to keep quiet lest we betray ‘our’ men, when really, we are ‘their’ women. We pretend misogyny is the monopoly of the White Western Man, which is between you and me, deeply unfair to the many, many, many other men around the world who really are doing their very best to keep up with the patriarchal race. United Colours of Patriarchy.

And most importantly, what happened to us women not to know who we are? Can the humans who can’t even activate a dishwasher really be so powerful to make us believe they are us? We are at the brink of one of the biggest denials in human history, perhaps worse than the denial of heliocentrism or Earth’s sphericity: the denial of the existence of two sexes.

Those — pornography, sexual sadism, queer and identity politics — are just a few of the issues Sheila Jeffreys has written about, on which she reflects in her autobiography and that compelled me to add my own thoughts in this review. So, talking about emotional states Sheila Jeffreys’s pen leaves you in, this time I feel bummed down and a little scared, like a latent danger whose nature we can’t really grasp is looming on the horizon. Is it the summer heat, the idleness of August? The book got me ruminating. How did we regress so much? The end of a dream is one chapter of the book. Are we women ready to wake up?

Despite the setbacks Sheila Jeffreys talks about, her autobiography is a call for action. The book might leave you nostalgic if you’ve experienced the past movement, it might bring you down if you wish you did, but the renewed energy that transpires from it, the achievements it reports but also the gravity of what is currently going on are invitations to get up, organise and advance. We must get up. Because we achieved so much and there is still so much to do.

Yağmur Uygarkızı

30 August 2020