HOW WOMEN GOT THE VOTE: THE STORY AFTER FEBRUARY 6th

How women got the vote: The story after February 6th

February 2018

by Kirstie Summers

February 6th marks the 100 year anniversary of the first time women were allowed to vote in the UK. The Representation of the People Act in 1918 expanded the electorate to include virtually all men regardless of income or status, and offered 8.4 million women the right to vote for the first time in history.

That same year, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act was also passed, which allowed women to stand as candidates and be elected as Members of Parliament. Constance Markievicz was elected to the Commons that same year, but as a member of Sinn Fein she refused to take her seat.

Constance Markievicz

Just a year later, Viscountess Nancy Astor took a seat in the Commons in the December 1919 by-election.

While these events were undoubtedly monumental steps forward for women’s rights in Britain, they came with a lot of restrictions.

The Act specified that “Women over 30 years old received the vote if they were either a member or married to a member of the Local Government Register, a property owner, or a graduate voting in a University constituency.”

Although 8.4 million women were allowed to vote, making up 43% of the electorate at the time, it was only 40% of the total number of women in the UK at the time.

A new organisation called the National Union of Societies for Citizenship was established shortly after these acts were passed. It advocated for equal voting rights for women and men, for the abolishment of the restrictions placed on female voters, as well as equal pay laws, fairer divorce laws and an end to discrimination against women in employment.

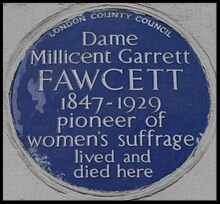

In March 1919, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, which had been integral to getting any women the right to vote, became the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, and Eleanor Rathbone took over as president from Millicent Fawcett. Under the new name, the organisation fought for more equal rights for women, including equal pay, the introduction of pensions for widows, the legal recognition of mothers and equal guardians of their children and other imperative legal rights.

The lobbying of these groups was evidently effective, as it was only 1919 when the Sex Disqualification Removal Act was passed. This made it illegal to exclude women from jobs based on their gender, meaning that women could now become solicitors, barristers and magistrates.

But the NUSEC wasn’t met with complete success.

Despite having close links to Ramsay McDonald, leader of the Labour Party, which had a minority government at the time, an attempt to pass a law to give women equal voting rights failed in 1924.

It was not until 1928 that women were finally granted the rights that they had fought so long and hard for. Many of the women who had been a part of the struggle for equal rights had died by then, including figures whose efforts are still celebrated today, including Emily Davis and Emmeline Pankhurst.

The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act was introduced in March 1928 and officially became law on July 2nd. It gave women complete electoral equality, so that all women over the age of 21 years old were could now legally vote, regardless of whether or not they owned property.

Millicent Fawcett, the original leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, famously wrote in her diary:

“It is almost exactly 61 years ago since I heard John Stuart Mill introduce his suffrage amendment to the Reform Bill on 20 May 1867. So I have had extraordinary good luck in having seen the struggle from the beginning.”