WHO WAS ANNE LISTER?

Republished with thanks to Jill Liddington

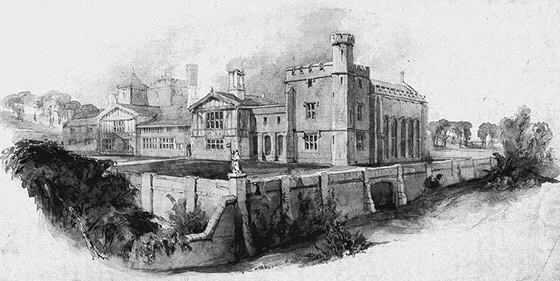

Photo: Shibden Hall, Calderdale Museums

Ever since her death in 1840, Anne Lister of Shibden Hall has exerted a magnetic attraction. The newest portrayal is Sally Wainwright’s BBC TV drama series on Anne Lister in the 1830s, to be broadcast in 2019. The series, Gentleman Jack, was inspired by my Female Fortune (1998) and Nature's Domain (2003).

The most powerful magnet remains her daily diaries. These run to no fewer than four million words, much of it written in her own secret code. Anne Lister’s code was not cracked till fifty years after her death.

Eventually it was deciphered in the 1890s by John Lister, who had inherited the Shibden estate. The diaries had been hidden behind panels in the Hall. Once cracked, the coded passages revealed Anne Lister’s daring lesbian affairs. Homosexuality was deeply shocking to late-Victorians, their fear of family scandal sharp. The diaries were apparently replaced back behind the secret panels at Shibden. Certainly, a forty-year silence followed.

Drawing of Shibden Hall, 1836, by John Harper (reference SH:2/M/2)

West Yorkshire Archive Service, Calderdale

Meeting Anne Lister

I moved to Halifax in 1980. Naturally a visit to Shibden followed - and I began to hear about this extraordinary woman, living on my very doorstep! Yet it was only in 1984, when the Guardian ran an article, ‘The two million word enigma’, that I became aware of the diaries. It warned: ‘many a curious amateur’ has retreated ‘thoroughly demoralized… before deciphering a single page’.

Then books began to be published - notably Helena Whitbread’s I Know My Own Heart (1988). Her edited diaries of the young Anne Lister (1817-24) really sparked my interest. And in 1989, a Halifax Antiquarians’ panel on Anne Lister aroused my curiosity yet further - especially about what editors had left out. I visited Calderdale Archives in Halifax where the Shibden papers are stored. I plunged in - starting with a rough word-count. To my absolute horror, the journals turned out to be not two but four million words!

By now I was gripped. I realized a full transcription was far too ambitious. Instead, I opted to transcribe three short selections from the diaries. The first, opening in 1806 when Anne Lister was just fifteen, showed how her secret code evolved and recorded her intimacies with other teenage girls.

The second section was from 1819, covering the tensions around the Peterloo Massacre and her complex flirtations with other women.

The third was from late-1832, recording both the first parliamentary election after the Reform Act, plus a maturer Anne’s courtship and seduction of neighbouring heiress Ann Walker.

For each section, I examined the diaries’ portrayal of Anne Lister, comparing these with the images presented by editors - from John Lister on. I remained hooked by Anne’s extraordinary life: dazzling worldly achievements plus unbuttoned lesbian affairs.

Gentleman Jack: from History Workshop to HBO

Presenting the Past

Presenting the Past was published in 1994, with a second edition in 2010, and then a new eBook version in 2018 - making this Anne Lister classic readily available to readers everywhere.

Presenting the Past tells the dramatic story of how the diaries survived after Anne’s death in 1840; how the code was finally cracked in the 1890s; and how since then, successive generations of editors and historians have each offered their own version of the extraordinary Anne Lister.

Plunging the reader into the Archives, Presenting the Past offers the very first critical reappraisal of these dramatically different images of Anne Lister - and asks how and why earlier editors selected their version? Everyone seems to want to present their own portrait of Anne Lister!

These versions were largely shaped by shifting attitudes to homosexuality. John Lister died in 1933, taking his knowledge of the coded diaries to his grave. Halifax Borough now became owners of Shibden - and so of the of Anne Lister papers. Yet even as late as 1964, the Halifax Town Clerk suppressed public knowledge of the coded sections. For it was not till 1967 that male homosexual acts were finally decriminalized. Lesbian relationships had remained untouched by criminal law, yet were shrouded in prejudice and secrecy.

Finally, in summer 2017, LGBTQ celebrations on the fiftieth anniversary of decriminalizing male homosexuality greatly widened public fascination with Anne Lister:

Professor Alison Oram, Leeds Beckett University, on Presenting the Past:

‘Anne Lister of Shibden Hall… was highlighted in our Historic England online exhibition, “Pride of Place: England’s LGBTQ Heritage”. I warmly welcome this new edition of Jill Liddington’s classic work on Anne Lister, tracking the changing reception of the diaries’ revelations about her sexuality and her bold and confident lesbian affairs - across 150 years.’

Female Fortune

I remained hooked by the compelling Anne Lister. Female Fortune (1998), presenting the 1833-36 diaries, dug deep into Anne’s world - revealing exactly how she operated to get what she wanted. As one book reviewer’s headline pronounced: ‘She was butch, “married” an heiress and ran her own business. Oh, and it was 1835’ (Independent on Sunday, 1998). Later, on ‘Desert Island Discs’ (2014), Sally Wainwright chose Female Fortune as the book she wanted to take with her if she was ever trapped on a desert island.

Nature’s Domain: Anne Lister and the Landscape of Desire

However, the 1832 diaries continued to intrigue me. I was repeatedly summoned back to them - by other Anne Lister projects. These included a Channel 4 history of homosexuality programme; a digital ‘Yorkshire Women’s Lives On-line’ project; and meeting scriptwriter Sally Wainwright in 2001. She wanted to portray Anne Lister in the mid-1830s, and plied me with enthusiastic questions as we walked round Shibden in the rain.

During 2002, all three projects persuaded me to go back to crucial months in 1832: April to New Year’s Eve. I dug out my old faint microfilm print-outs, and re-visited my early faltering attempts to make sense of Anne Lister’s startlingly diverse daily life then.

One by one, Anne’s women friends had married. In April 1832, she found herself bitterly betrayed by yet another woman’s marriage plans. Despondent, Anne made her way back home to her dispiriting family and equally dispiriting Shibden Hall. Aged forty-one, her romantic youth was over. But re-acquaintance with neighbouring heiress Ann Walker changed all that.

Nature’s Domain (2003) tells the story of how in 1832 Anne Lister came into her own. It inspired the opening episodes of Sally Wainwright’s new BBC TV drama series, currently being filmed at Shibden. Gentleman Jack will be broadcast in early 2019.

So is Anne Lister an inspirational feminist icon, an LGBTQ heroine for our times? And is she really the first modern lesbian?