Love, Work and Activism as a Socialist Feminist: Sheila Rowbotham

A book review of

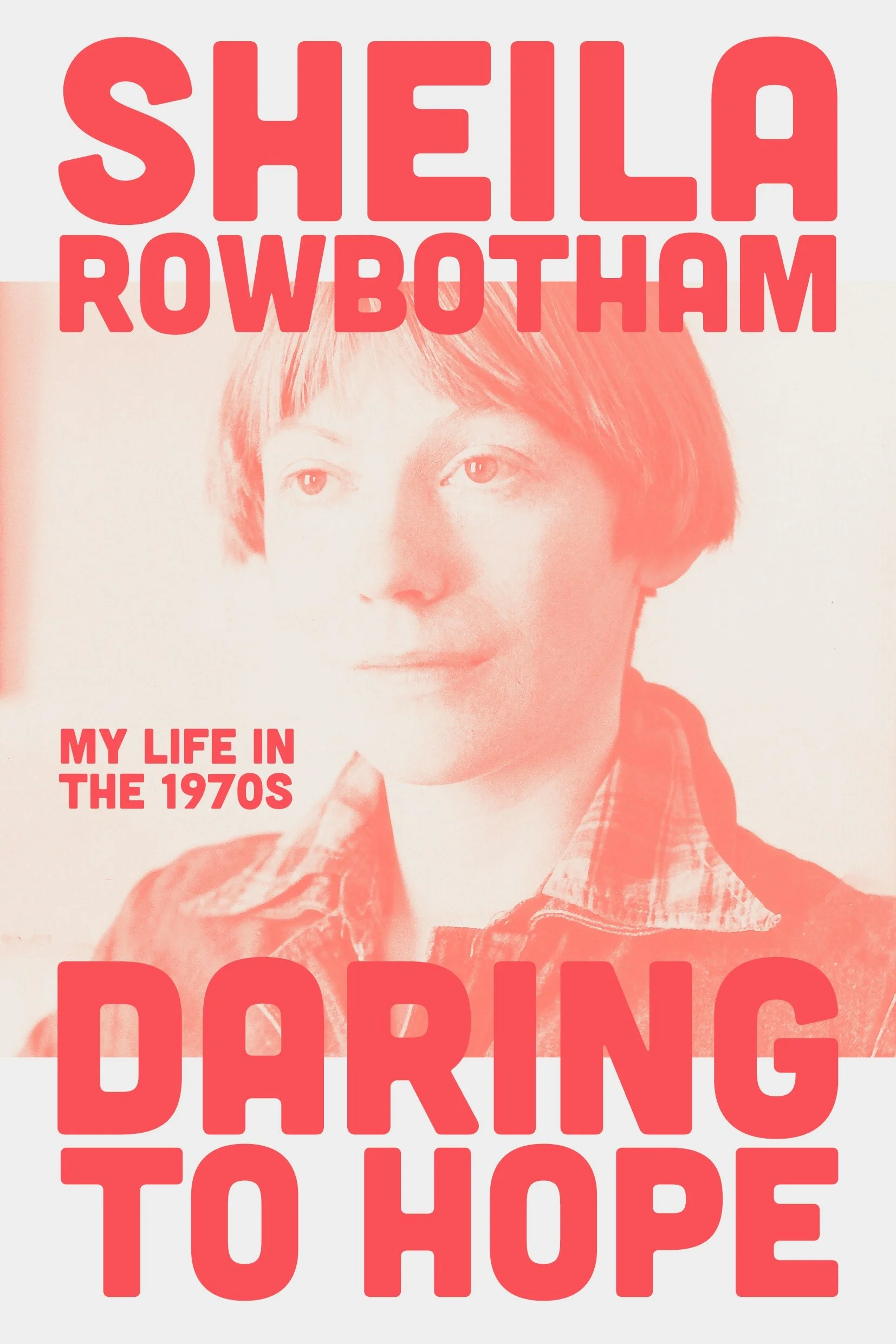

Daring to Hope: My Life in the 1970s

by Sheila Rowbotham

Published 9th November 2021 by Verso Books

Reviewed by: SD

“I was still preoccupied with tracing the elusive courses of how radical ideas are communicated and then translated and transformed in everyday usage. Such spoors are easy to miss. But when Paul’s mother, Norah Atkinson, wrote thanking me for renewing her Spare Rib subscription that June, adding ‘I sometimes feel as though I am in a world of my own – till I read about other women’s interests’, I knew she was describing just that sense of recognition which could signal new ways of seeing.” Sheila Rowbotham, Daring to Hope: My Life in the 1970s p179

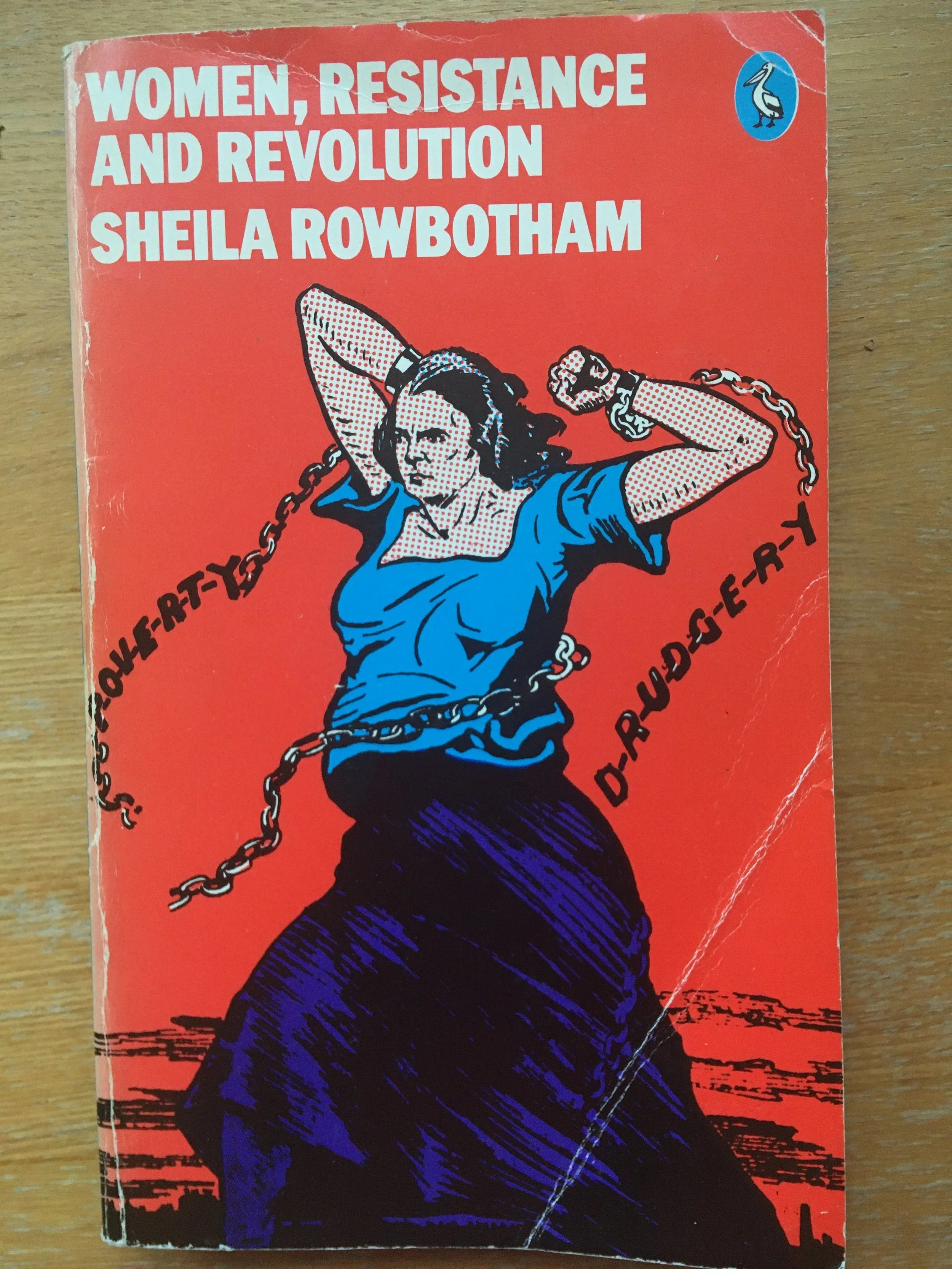

Nearly two decades ago, I was given Sheila Rowbotham’s Women, Resistance and Revolution when one of our teachers in high school donated secondhand books to us all just before graduation. I can’t recall why that particular text came home with me, but I suspect I was attracted to the cover image of a woman breaking free from chains, in a blue dress against a red backdrop. My copy is from 1974. It has a sticker listing its price in Danish kroner. I sometimes wonder about its previous owners. Perhaps they were international feminists? To my great shame, I’ve still never gotten past the first couple of pages, although I still admire the artwork. For most of my life, when I found reading time I would prefer fiction. Many theory and nonfiction works struck me as too dry for leisure, or requiring strenuous intellectual demands for which I would not receive academic credit. So the first book by Sheila Rowbotham I’ve actually read is her new memoir, Daring to Hope: My Life in the 1970s, which found its way to my bookshelf almost twenty years later. In a quirk of fate, this memoir covers the period when Sheila was writing Women, Resistance and Revolution, and much more, besides.

As a woman with near-zero understanding of the differences between Marxist and Leninist ideas, much less a concern for what Trotsky thought, I’ve tended to give socialist feminism a wide berth. I was initially worried Daring to Hope would leave me feeling rather stupid. Upon settling into the text, however, those fears quickly abated. What I found was a sparkling account of the arc of the Women’s Liberation Movement during the 1970s, from its electric and heady earlier days to an eventual dissipation of its energies, narrated by a deeply embedded woman who was resourceful, emotionally open and frequently made me laugh out loud. Stalwart feminists, whose names are known for their important contributions to the cause of women, can easily be perceived as being completely different in their natures to perfectly ordinary women like myself. So the marvellous part of this memoir was being able to connect through text and history with this intellectual champion, to meet her as a younger woman with some preoccupations I recognise: trying to understand what feminism means, learning with other women, making domestic ends meet, negotiating emotions and relationships, agitating for change in the world and balancing an endless number of tasks that come from a tendency to over-commit. Despite feminist progress, in many ways questions women grappled with in the 1970s linger on: “How to find ways of snatching happiness from the future so as not to be consumed by our own bitterness against circumstances in the present?”(p80)

The book centres on a personal narrative, but is nicely balanced with wider reflections on politics, feminism and the women’s movement alongside contemporaneous poetry, giving the reader an insight into not only what Sheila was engaging in, but how this time was experienced, felt, processed. Throughout, specific details place the reader in the story and references to source material are diligently marked, which is perhaps unsurprising given the author is an historian. As an Islington resident and fan of women in country music myself, I took pleasure in knowing some locations Sheila mentioned and the discovery of a mutual fondness for Loretta Lynn (“Hey Loretta” was stuck in my head for the rest of one chapter). I remain less interested in Althusser or the challenges in reshaping socialism. But the memoir did make me want to learn more about the latter, because I grew so fond of the storyteller and greatly admired the skilled craftswomanship of her writing.

The first half of Daring to Hope fizzes with a special energy when it covers the Women’s Liberation Movement: women meeting, organising, theorising and calling for action. Consciousness-raising groups are formed throughout the country, blending the personal and political. Non-hierarchical, women-centred ways of interacting are trialled out, often presenting challenges of their own. Inter-generational and international links between feminists are forged. Women’s groups fighting multiple injustices, such as racism and classism, call for further action to end the interconnected oppressions affecting women, a kaleidoscope of unfairness that impairs our ability to flourish. In the second half of the book, with wane of the momentum of Women’s Liberation palpable in the text, Sheila may perhaps raise some feminists’ eyebrows. She emphasises feminism’s need to work with men and places responsibility for the fading of the movement on separatist revolutionary feminists: “Believing that they alone held politically correct views, they denigrated their opponents as ‘bad’ women. Moral imperatives hardened into an authoritarian rhetoric.” (p247) The task for an interested reader, then, would be to find the account of a revolutionary feminist from this same time.

The lessons for me from this memoir include the strength of women when we connect together, the importance of finding the mutualities in our stories while respecting each other’s differences. That our lives are very different, but we recognise rhymes, patterns, themes. Practically, I think women today should keep their diaries, save their correspondence and make notes. Don’t throw words out, as who knows whether in the future our time, too, will be known as significant in Women’s Liberation. In any case, we need to keep records of a plurality of women’s experiences and perspectives.

I also need to read all my books. I pledge to rectify my error and be finished with Women, Resistance and Revolution before the end of this year.