Women's rights violations in Sudan

By Khadija Khan, a journalist and commentator based in the UK. With thanks to Islah Hamad for enabling us to hear from Women in Sudan .

The horrendous experiences of Sudanese Women of discrimination and state brutality continue to go unreported while the country's turmoil rages, making them invisible to the rest of the world.

Sudan has been in a state of civil war for several months due to hostilities between the military, led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), commanded by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (also known as Hemedti). The conflict, which started in the capital, Khartoum, and spread to Darfur, is causing widespread destruction and devastation.

Most of the victims of the ongoing civil war are now women and girls. Pro-democracy demonstrations against a military takeover that toppled the civilian transitional government in 2019 marked the beginning of the crisis. During these demonstrations, there has been disproportionate sexual and gender-based violence against women and girls.

More than a million people have been driven from their homes as the Sudanese civil war continues. Many people have sought safety from the violence in the surrounding nations of South Sudan, Egypt, Ethiopia, the Central African Republic and Chad. But women continue to be caught in a cycle of unabated violence.

The brutal suppression of the peaceful rallies that demanded a government made up of a majority of civilians, rather than the military, brought this dreadful scenario to a peak. With the assistance of other regular troops, the RSF troops brutally dispersed the peaceful protesters, killing and injuring hundreds of people in the process.

There have been dozens of reports of women being sexually assaulted and raped during the many violent attacks. Security forces in Sudan have consistently denied firing live ammunition at peaceful protestors.

One rape survivor spoke to the BBC. ‘They were very barbaric. They took turns raping me under the tree where I had gone to gather wood to [make a fire to] keep warm,’ she said in a quivering voice down the phone line.

Mona Osman, who witnessed these crimes firsthand, has been in touch with me. She said, ‘The calm turned into terror, and I came to understand nothing except for the sounds of tanks approaching the house, and the electricity was cut off. On the side of the road were burnt vehicles, and the fire was still burning in them. There were large quantities of corpses in the open air. Fear and the smell of death were everywhere. We have no money or a home. All we had is lost. Our future is lost, and our dreams are lost. There is no food or water, and all the residents of the capital, Khartoum, left. We all became homeless, inside or outside Sudan. All we want now is to live in safety and peace, away from the sounds of guns and planes.’

Another eyewitness Sarah Hamid said, ‘Our neighbours’ daughters had been kidnapped from their house and we can expect anything from them. The smell of war and death was sickening, dead bodies all along the road, burnt vehicles smoking up all around us. Families with their children crossing long distances on foot to flee the war. Days of our life had been spent in tears, fears and it will stick in our memories for ever. Now we are still trying to find peace and cope with grief, loss and trauma.’

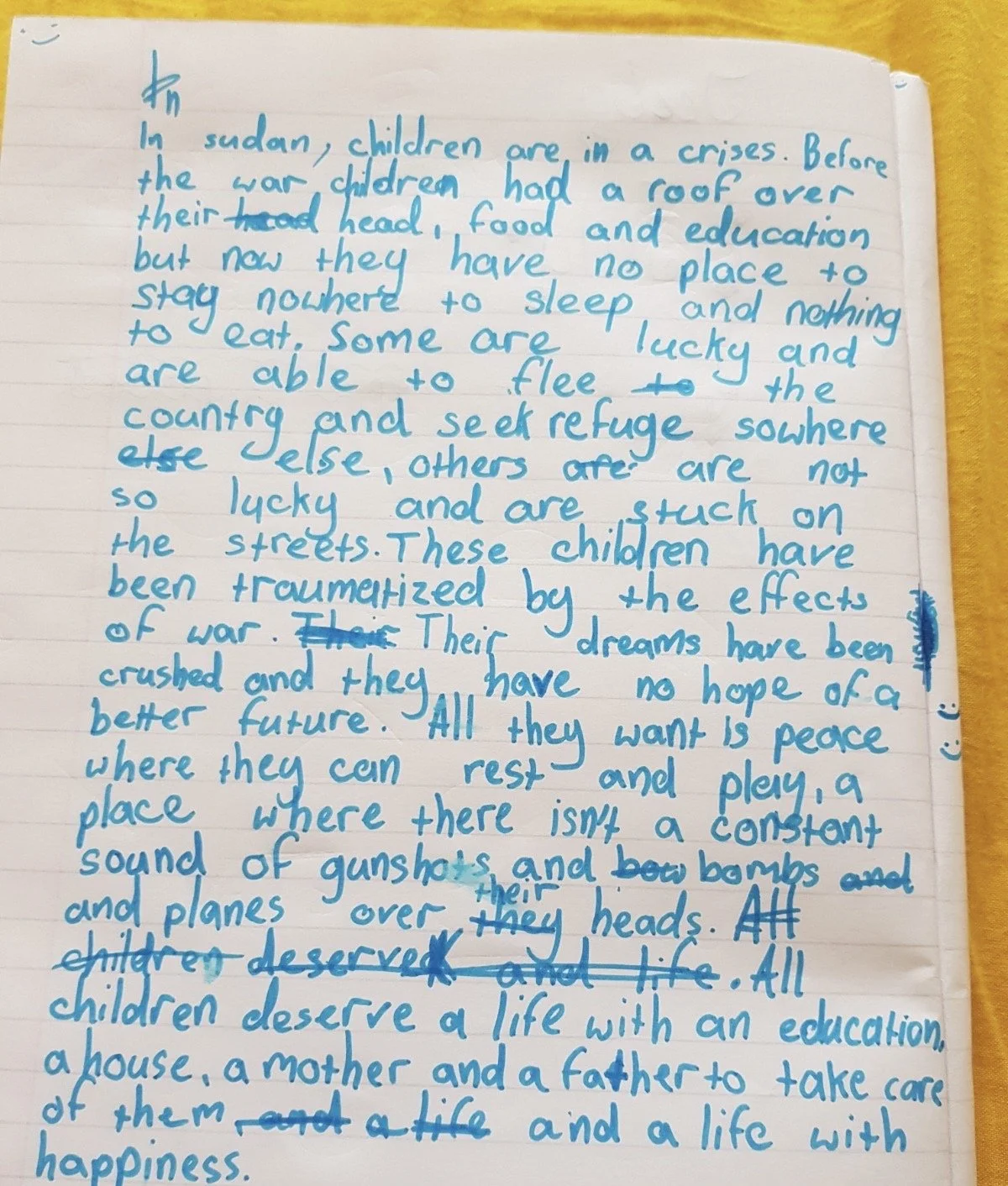

It is even more devastating to read the thoughts of a ten-year-old Sudanese girl, born and living in the UK but who has visited Sudan many times, reflecting on the circumstances of the children that she could so easily have been one of.

She writes: ‘In Sudan, children are in a crisis. Before the war, children had a roof over their head, food and education, but now they have no place to stay, nowhere to sleep, and nothing to eat. Some are lucky and are able to flee the country and seek refuge somewhere else. Others are not so lucky and are stuck on the streets. These children have been traumatised by the effects of war. Their dreams have been crushed and they have no hope of a better future. All they want is peace where they can rest and play, a place where there isn’t a constant sound of gunshots and bombs and planes over their heads. Children deserve a life with an education, a house and a mother and a father to take care of them and a life with happiness.’

The current crisis might have started just a few months ago but Sudan has a long history of discrimination against women.

In Sudan, President Jaafar Nimeiry, who had come to power in 1969 in a leftist coup, would end up imposing Sharia law by 1983. In the early 1990s, a religious police force was established in Sudan, leading to further restrictions for women around clothing and their ability to move freely in society.

This change reflected the evolving cultural and religious landscape of Sudan, which resulted in the loss of women's already limited freedoms in a conservative society.

Religious discrimination against women is a persistent issue in Sudan, often driven by religious beliefs. Religious laws have long been used by leaders to exert control over women, and sexual assaults on women have regularly been used in Sudan to settle political issues.

Throughout history, women have fought courageously and valiantly for the rights and freedoms that are unjustly taken away from them. Despite the difficulties they encounter in challenging state-approved violence, women persevere in their efforts to attain justice, security, safety, and their rightful place in society. Sudanese women have been vocal against these injustices during the recent pro-democratic protests.

For years, these women have been actively participating in peaceful protests to demand freedom, peace and justice. It seems that their voices have fallen on deaf ears. They have condemned the use of women's bodies as political pawns. They have refused to be sacrificed at the altar of religious modesty while demanding accountability and justice for those responsible.

Senior United Nations officials have expressed shock and condemnation at the growing reports of gender-based violence in Sudan including conflict-related sexual abuse against displaced and refugee women and girls.

The situation in Sudan appears to be intractable. Even if the conflict is resolved, it could potentially turn Sudan into a battleground for proxy wars among Middle Eastern countries. Despite their claims of pursuing peace, the middle powers in the region continue to arm their allies.

In such a corrosive environment, access to services and support is severely hampered, increasing risks for women and girls. Gender-based violence, sexual exploitation and abuse have increased many times over. In such a dire situation, the safety and well-being of Sudanese women and girls is a major concern.

Although humanitarian organisations have condemned sexual abuse used to terrorise civilians as a weapon of war, there are hardly any effective safeguards in place to protect these defenceless women. Despite all odds, women in Sudan are still fighting institutionalised inequality and pervasive misogyny that has its roots in religious discourse. The ever-unfolding women’s rights crisis in Sudan demands attention from the international community.