Being Women in a Clandestine Detention Centre - The case of ESMA

By Alessandra Viggiano, the Minister for Culture, Gender and Human Rights in the Argentinian Embassy, UK.

In this text, I would like to address an aspect of gender perspective not commonly mentioned in the narratives of the democratic consensus Argentina reached after the dictatorship of the 1970s. Until just a few years ago, we alluded to sexual violence practices and different forms of gender violence as “part” of a crime against humanity or even as a “tool” for those crimes. Hence, the perspective of the victims of sexual crimes during the dictatorship was absent from the truth, justice, memory and reparation process. Now, however, we are able to consider those offences as crimes in themselves and as an integral part of the systematic plan carried out during the dirty war. Through this perspective, women that were kidnapped and tortured are able recover their voices and acquire a sense of agency.

In Argentina, one of the bloodiest military dictatorships of the last century took place between 1976 and 1983, with 30,000 people murdered or disappeared before it ended. During that period, one plan that was central to the repressive apparatus deployed by the military dictatorship was the so-called ESMA, the Officers' Casino building, that stands today as a national historical monument, testimony to state terrorism and a source of judicial evidence in cases of crimes against humanity in Argentina. Located on one of the main access roads to the city of Buenos Aires, it was the repressive nucleus of the clandestine detention, torture and extermination centre. With a perversity that is all too apparent, this building had a dual function, serving as both the place of recreation for high ranking naval officers and at the same time housing disappeared detainees.

Its symbolic power is based on the building’s location in the centre of Buenos Aires and its massive proportions, which allowed 5,000 Argentine citizens to be kidnapped, tortured, killed and/or disappeared without any perceptible impact being felt on the day-to-day life of Buenos Aires. Some of the most horrific stories from the dictatorship took place at ESMA: babies were born in inhuman conditions, women were held captive as slaves of the military authorities and prisoners were thrown alive into the sea. Visiting the place is an emotional roller coaster because it is preserved as it was during that period between 1976 and 1983. Letters, pictures and graphic exhibitions give testimony to the grave human rights violations perpetrated there and the systematic plan to steal children born in captivity.

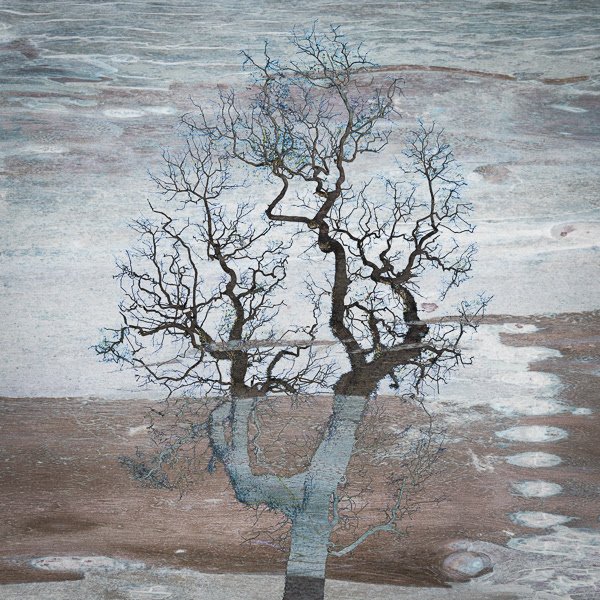

There is a special exhibition on at ESMA at present, called “Being Women at ESMA II - Time for Encounters”, that reflects on the specific nature of the state violence that was carried out against these women. The exhibition reinstates them with a sense of agency and a voice as an active subject in the fight for democracy. The women survivors spoke of torture, murders, the appropriation of newborns, everyday violence and inhumane treatment. However, it took them longer to report sexual violence and different forms of gender violence. This project incorporates those absent voices and includes them in the reparation process. Memories of the recent past, ways of processing the past, and the strong imprint of the human rights paradigm are elements that are still central in our political and social debates. During the Trial of 1985, the courts considered the violations as an integral part of the torture. In the eighties, the cultural framework classified sexual violence as a form of torture without the specificity of it constituting gender violence. In 2001, with the reopening of trials against humanity, the gender dimension began to slowly enter the courtrooms. It was only in 2010 that the first conviction of a repressor as a rapist came to pass in the country. And then, in 2011, followed convictions for sexual abuses carried out in the clandestine centre as systematic practices perpetrated by the state as part of a wider plan of repression and extermination. Despite the numerous complaints made in each of the trials, still no one has been convicted of sexual crimes from the members of the ESMA Task Force.

I wanted to address the memory of these women for two reasons:

My country is looking to gain support for ESMA to be nominated to the UNESCO World Heritage List. This would serve to promote international awareness of the crimes against humanity committed by the civic-military dictatorship that ruled Argentina between 1976 and 1983.

In dialogue with the new sensitivities that the women's movement is awakening at present and its demands in the street, the exhibition facilitates a dialogue with the younger generations that is currently occupying the streets of Argentina with its feminist rallying cries:

#NiUnaMenos

#VivasNosQueresmos

#AbortoLegalEnElHospital

#MemoriaVerdadJusticia